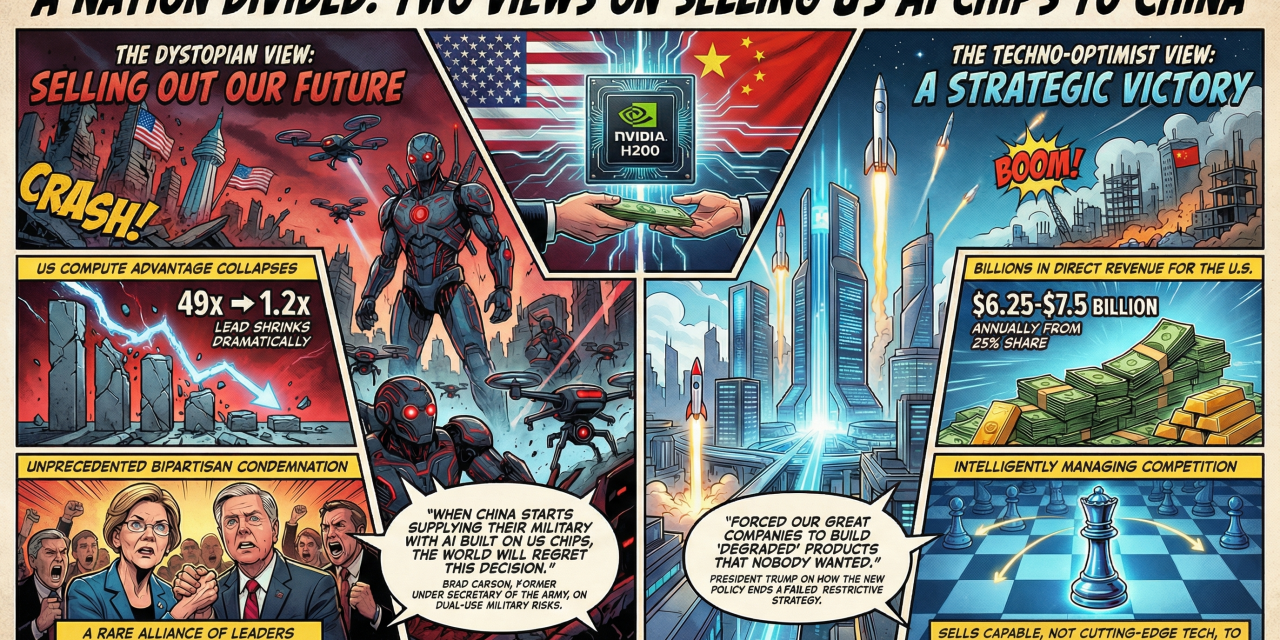

I’ve watched his administration navigate complex trade negotiations, and I understand the logic of keeping American companies competitive globally. But this one? The decision to allow NVIDIA’s H200 chips to flow to China in exchange for a 25% revenue cut? I genuinely don’t get it. And apparently, neither do the experts from both parties who’ve spent their careers thinking about this exact problem.

Let me walk you through what happened, why the numbers matter, and why I find myself agreeing with Elizabeth Warren and Lindsey Graham at the same time, which should tell you something.

What Actually Happened

On December 8th, 2025, President Trump announced on Truth Social that the United States would allow NVIDIA to ship H200 chips to “approved customers” in China. His exact words: “$25% will be paid to the United States of America. This policy will support American Jobs, strengthen U.S. Manufacturing, and benefit American Taxpayers.”

On December 8th, 2025, President Trump announced on Truth Social that the United States would allow NVIDIA to ship H200 chips to “approved customers” in China. His exact words: “$25% will be paid to the United States of America. This policy will support American Jobs, strengthen U.S. Manufacturing, and benefit American Taxpayers.”

Sounds reasonable on the surface, right? American company makes money, Treasury gets a cut, everybody wins.

Except here’s where it gets strange. On that same day, literally the same day, the Department of Justice unveiled “Operation Gatekeeper,” a prosecution of a $160 million smuggling ring that had been illegally exporting these exact same chips to China. U.S. Attorney Nicholas Ganjei didn’t mince words: “These chips are the building blocks of AI superiority and are integral to modern military applications. The country that controls these chips will control AI technology; the country that controls AI technology will control the future.”

So we’re simultaneously prosecuting people for smuggling chips to China while announcing we’ll sell them legally for a cut of the revenue. I’m not a national security expert, but that’s a level of policy incoherence that makes my head spin.

The “Lagging Chip” Argument Doesn’t Hold Up

White House AI Czar David Sacks defended the decision by calling the H200 a “lagging chip”—one that “was state-of-the-art a couple of years ago, but now it’s been superseded by the newer Blackwell architecture.”

That framing obscures some critical context. Let me break down what we’re actually talking about here.

The Institute for Progress released a comprehensive report on December 7th, just before the announcement. Here’s what their analysis shows:

Performance Comparison:

| Chip | FP8 Performance | Export Status Before Decision |

| H20 (China-specific) | 296 TFLOP/s | Required export license, limited quantities |

| H200 | 1,979 TFLOP/s | Banned |

| Blackwell B300 | 5,000 TFLOP/s | Reserved for US/allies |

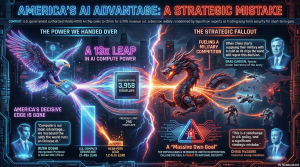

The H200 delivers roughly 6x more computing power than the H20 that China previously had access to.

But here’s where the strategic math gets devastating. According to the same Institute for Progress report:

- Before this decision: The US held a 21x to 49x advantage in 2026-produced AI compute over China (depending on how you count Blackwell’s advanced features)

- After unrestricted H200 exports: That advantage shrinks to 1.2x to 6.7x

We’re not talking about a minor adjustment here. We’re talking about collapsing our compute advantage by up to 94%. That’s not monetizing a lagging asset—that’s liquidating a strategic position.

China Can’t Build This Themselves

Here’s what makes the timing so confusing to me. According to Huawei’s own three-year roadmap, they’re not planning to produce a chip matching the H200’s performance until Q4 2027 at the earliest.

The Institute for Progress puts it starkly: due to severe manufacturing bottlenecks, China’s domestic AI chip production will reach only 1-4% of US production in 2025 and 1-2% in 2026.

So we’re handing China chips they literally cannot make themselves, during the most critical acceleration phase of the AI race, in exchange for… what exactly? A revenue share that might bring in $6-7 billion annually? Against a technology lead worth potentially trillions in economic and military advantage over the coming decades?

The Bipartisan Alarm Bells

What really caught my attention was the political response. This isn’t a partisan issue—people who normally can’t agree on anything are united in concern.

What really caught my attention was the political response. This isn’t a partisan issue—people who normally can’t agree on anything are united in concern.

Republican concerns:

- Senator Josh Hawley: “Serious concerns.”

- Senator Lindsey Graham: “Alarm bells go off in my head.”

- Rep. John Moolenaar (Chair, House China Committee): Formally questioned the information basis for the decision.

Democratic concerns:

- Senator Elizabeth Warren: “Selling out US security.”

- Senator Mark Warner (Vice Chair, Senate Intelligence): Called it “a mistake.”

When Warren and Graham find common ground, it’s worth paying attention.

This bipartisan opposition materialized into the SAFE Chips Act, introduced by Senators Pete Ricketts (R-NE), Chris Coons (D-DE), Tom Cotton (R-AR), Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), Dave McCormick (R-PA), and Andy Kim (D-NJ). The bill would block advanced AI chip exports to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea for 30 months.

Senator Coons captured the stakes: “As China races to close our lead in AI, we cannot give them the technological keys to our future through advanced semiconductor chips.”

The Official Justification Keeps Shifting

The administration’s defense has evolved through several arguments, none of which seem to hold water under scrutiny:

Argument 1: “We’ll keep Blackwell for ourselves”

True, the newest Blackwell and upcoming Rubin chips aren’t part of this deal. But as Chris McGuire from the Council on Foreign Relations notes: “If the United States sells AI chips to China that are 18 months behind the frontier, it negates the biggest U.S. advantage over China in AI.”

The H200 isn’t 18 months behind—Chinese AI labs could use H200s to build training supercomputers matching American ones for roughly 50% extra cost, according to the Institute for Progress. A cost premium the Chinese government would happily subsidize.

Argument 2: “This will take market share from Huawei”

This is the logic Sacks articulated: keep Chinese firms dependent on American chips rather than letting them develop their own.

But here’s the irony—even Sacks himself acknowledged that China appears to be “rejecting” the H200s to “prop up and subsidize Huawei.”

And the Financial Times reports that Beijing is planning to limit domestic access to H200s, requiring buyers to justify why domestic chips can’t meet their needs.

So we might be offering chips that China won’t fully embrace anyway, while simultaneously validating their strategy of technological self-reliance.

Argument 3: “The previous policy hurt American companies”

Trump argued the Biden approach “forced our Great Companies to spend BILLIONS OF DOLLARS building ‘degraded’ products that nobody wanted.”

There’s a legitimate business concern here—Nvidia did develop the H20 specifically for the Chinese market under export restrictions. But the strategic calculus remains: is protecting Nvidia’s China revenue worth eroding America’s compute advantage?

The Precedent Problem

What concerns me most isn’t just this specific decision—it’s the precedent it sets.

Chris McGuire called it “a seachange in U.S. policy.” He elaborated: “This is the single biggest change in U.S.-China policy of the entire administration” and “a transformational moment for U.S. technology policy, which until now had been predicated on investing at home while holding China back. Now we are trying to win a race against a competitor who doesn’t play by the rules.”

We’ve spent years building an international coalition—working with the Netherlands, Japan, Taiwan—to coordinate restrictions on semiconductor technology to China. We asked our allies to sacrifice commercial interests for strategic alignment.

Now we’re monetizing the very technology we asked them to block. What message does that send?

Where I Land

I understand the complexity of global trade relationships and the legitimate interests of American companies. I get that complete technology denial is probably unrealistic and may accelerate the very self-sufficiency we’re trying to prevent. But the numbers here tell a clear story. We’re trading a 21-49x compute advantage for a 1.2-6.7x advantage. We’re giving China chips they can’t manufacture until 2027. We’re doing this while simultaneously prosecuting smugglers for the exact same behavior.

If this is 4D chess, I can’t see the board.

Former Under Secretary of the Army Brad Carson offered the most sobering assessment: “When China starts supplying their military with AI built on US chips, the world will regret this decision.”

Maybe there’s a strategic logic I’m missing. Maybe the administration has intelligence suggesting China’s domestic development is further along than public estimates. Maybe the revenue share mechanism contains enforcement provisions we haven’t seen yet.

But based on what’s publicly known, this looks like selling our most significant technological advantage in the defining competition of the 21st century, and doing it for quarterly revenue.